DocSpect

Full project description

Knowledge workers, such as auditors and financial analysts often need to review large collections of contracts containing complex clauses that mediate many day-to-day business transactions. While prior work across other applications has evaluated the benefits of human-AI collaboration when dealing with large amounts of data, there is a lack of human-centered approaches for contract inspection tools. I conducted qualitative interviews with six knowledge workers at a large enterprise to gain insights into their reviewing strategies, usage of tools and perception of AI. One of my key findings is the cross-functional use of contracts as a knowledge base for revenue recognition and forecasting, which in turn impacts business decisions. I designed a framework and interactive tool that supports knowledge workers in adopting a reviewing strategy that creates a more efficient and optimal business pipeline by considering forecasting uncertainty and the impact of contracts.

In order to gain more understanding into the contract reviewing process and its underlying mechanisms, we interviewed six professionals from our organization who were either responsible for reviewing contracts, or managed teams of knowledge workers. Among the six experts, two worked in Revenue Assurance, two in Forecasting & Planning and two in Procurement. The interviews, which were conducted via video conferencing, lasted about 30 minutes each. First, we asked participants about their role and daily tasks regarding contract inspection. Then we inquired about the volume of contracts they review. Next, we inquired about their reviewing strategy, and factors they consider when reporting revenue recognition forecasts. Finally, we asked participants for their thoughts on using an AI assistant to assist them in reviewing contracts. Each interview was attended by two of the authors, who took turns questioning participants. The two authors separately annotated and extracted common responses and themes that emerged from the interviews, then collaborated on consolidating these themes. For the sake of confidentiality, some details involving monetary values and stakeholder names have been anonymized.

Contracts as a knowledge base for business operations

Several operations in the business pipeline depend on contracts, which contain valuable information about the business. Knowledge workers review contracts to optimize the best deal for the company, or to determine if it is worth reviewing. S5 states that “We’ll analyze the contract, usage and whether the contracts are optimally designed. And then, when come a renewal time, we’ll build a strategy of what should be our approach. So in a lot of cases, we have gone and changed the structure of the agreement to suit our needs.” Moreover, a significant portion of the revenue of several enterprises stem from negotiated contracts. Participants mentioned that contracts serve as a reference document to ensure that revenue is being reported correctly and to forecast future revenue. S3 reports that “We have a [amount] revenue target I believe, and we’re responsible for the reporting of net revenue against that.”

A risk-based approach for a large number of contracts

This organization has between 12,000 and 15,000 negotiated contracts per year and knowledge workers have to prioritize which contracts to review. While their approach is not systematic, there is a general consensus on the nature and magnitude of risk factors to consider in order to minimize error in revenue recognition. S3 mentioned that on average, his team reviews 20 contracts per week and given the large number of contracts, they attempt to review 60–70% of their contract value in a given quarter. Knowledge workers tend to prioritize high-value contracts which lead to a more accurate revenue forecast. S1 states “We get a report from [external software] and anything that’s over total contract value of [amount] will show up in this report and be flagged to the analysts associated with the territory so they can go review that contract.” S6 admits that discarding all contracts below a certain value could pose some risk. They mention that “We don’t review contracts under [dollar value] unless the [external stakeholder] reaches out and involves this in the process. So for anything that we’re not getting involved in, we’re not looking at those. So we could be missing something potentially.” The presence of certain non-standard clauses can impact how much revenue is generated from the agreement, for example exclusivity clauses, auto-renew clauses, future purchases clauses and termination for convenience clauses. S3 states “One example [of clauses that affect revenue recognition] is the commitments to future purchases. If a customer is buying, say 1000 units of [product] and then in that same contract we give them a right to buy [product] at a discount in the future, then that would be relevant to my team, since it could cause a revenue adjustment.” Therefore, to improve the accuracy of revenue recognition, contracts containing these clauses need to be given more attention.

Perception of AI: some error is better than flying blind

Several steps and entities are involved in the contract reviewing process. The experts work with an external team to assist them in their reviewing process. A few of the knowledge workers we interviewed were also introduced to preliminary AI tool that flags Termination for Convenience (TFC) clauses, which allows both parties to terminate the contract at any point in time without any just cause, putting potential revenue from the contract at risk. The tool flagged contracts where a potential TFC clause was detected, but does not highlight the location of the clause in the contract, the uncertainty or explanation behind the detection. Several experts mentioned that their approach is to review all the suggestions from the tool. S6 mentioned that “At this point, the idea is to review all of them, because it’s still pretty new.” This highlights the lack on trust in the tool, in some cases due to its recency. Despite their over-vigilance in their usage of the tool, most participants agreed that it is useful to help them narrow their focus toward a subset of contracts. S5 stated “I mean [the tool] might not pull information from one or two contracts. But beyond that, I mean in any case, I’m flying blind unless I go and read all those 2000 contracts, right.” We also asked participants about how they would handle potential errors from an AI suggestion. Generally, participants highlighted that low precision is worse than low recall. S3 mentioned that “if [external contractor] tells us something has termination for convenience and it’s not there and we review it, in most cases, my team will get it right. On the other hand, if they don’t tell us and there is termination for convenience in the contract, we probably won’t see it. And then we’re more likely to have an error.”

We asked participants to describe an ideal tool that would assist them in reviewing contracts. Several participants mentioned that a useful tool would have the ability to compare a set of similar contracts. S5 mentioned that “Imagine we are looking at a whole category of about 5-6 suppliers of similar type, right. And we want to look at a holistic view if you want to do a comparison of the similar clauses.” Another feature that was highlighted by several participants is the ability to flag contracts to inform the user on where to allocate their attention. S4 mentioned that “say we have a health dashboard, this gives us those red, amber and, you know, green flags. For each of these, we wanna know what if this happened?.” S5 mentioned the importance of highlighting certain key terms in high stake contracts “So and all contracts where I do not have termination for convenience or all contracts where we have auto-renewal provision, all contracts where we do not have caps on increases for future purchase or future renewals. So that then I know where to focus on and we can plan it out and you know assign resources to go in and work on those. So any contract over [amount] where these clauses are not standard and we can say.”

Design Guideline I: Considerations for AI Uncertainty

UI Feature I: Reviewing Parameters

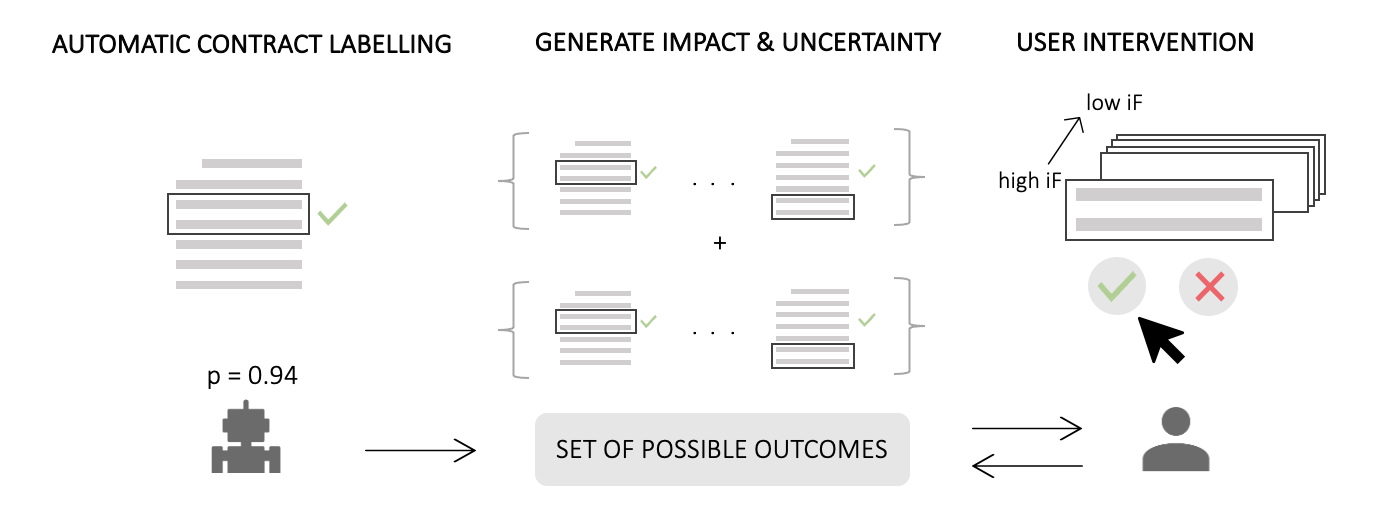

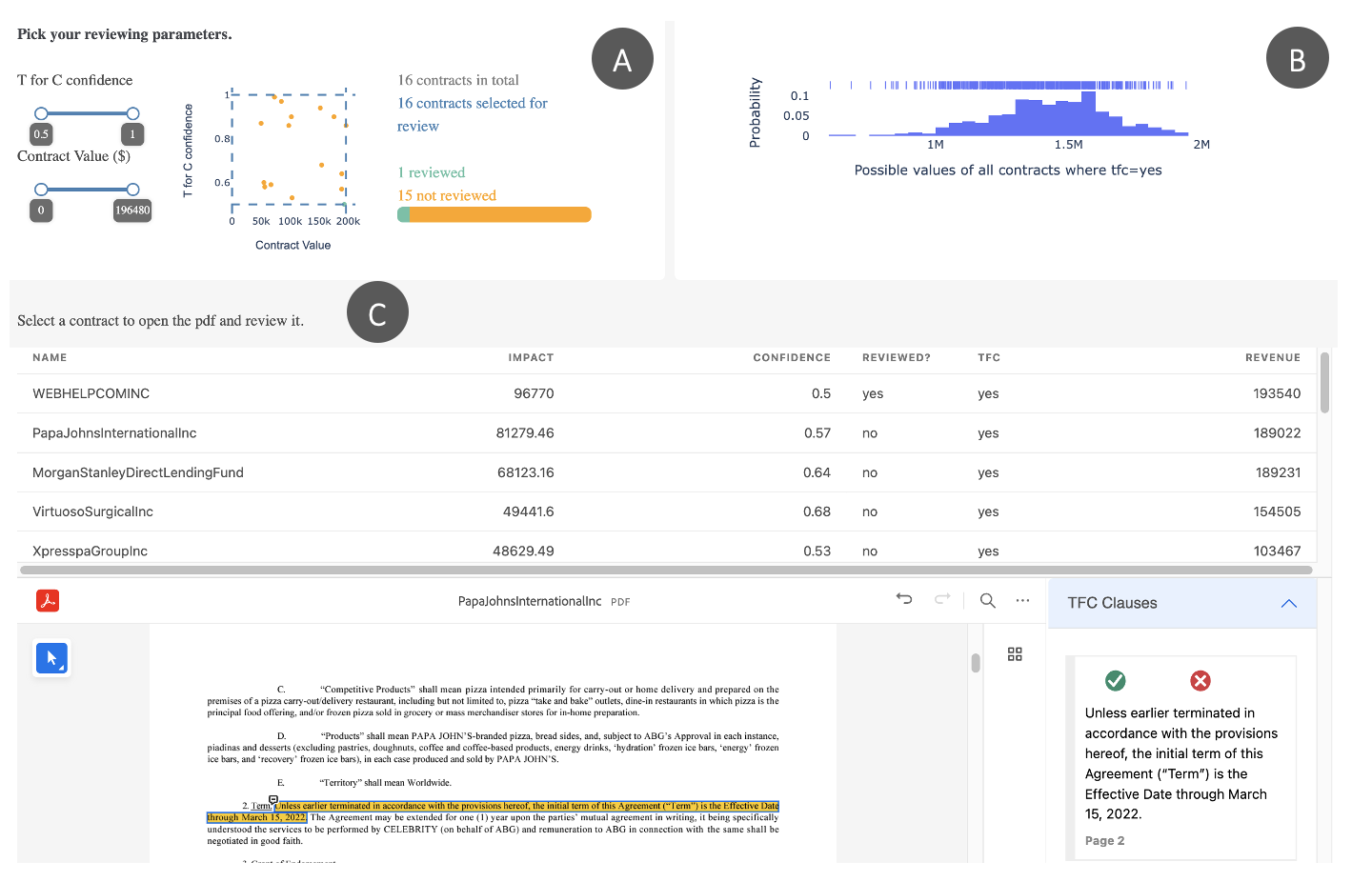

Imagine a scenario where a knowledge worker’s task is to detect the total revenue at risk due to the presence of TFC clauses. The AI is 0.95% confident that there is a TFC clause in contract A, which has a value of $2M. On the other hand, it is 0.6% that there is a TFC clause in contract B, which has a value of $1.5M. If the knowledge worker has to choose only one contract to review, they can weigh the AI confidence and contract value to determine the impact of each contract on revenue recognition. To effectively combine these risk factors, one approach is to compare the product of the uncertainty and the contract value such that iF = (1 − conf ) ∗ value where iF is defined as the impact (or risk) factor. Therefore, the knowledge worker should review contract B (iF = 600, 000) since the AI has a high accuracy in the presence of TFC clause in contract A (iF = 100, 000). We adopt this approach in our TFC prototype shown in figure 1, where the list of contracts in C) is sorted by iF . Since thresholds for AI uncertainty or contract value may vary, in A) we propose that knowledge workers input these corresponding reviewing parameters and define the set of contracts that they wish to review.

Design Guideline II: Communicating Impact on Forecasts

UI Feature II: Visualization of the set of possible outcomes

Suppose that a classifier is 80% confident that there is a TFC clause in contract A ($125,000) and 95% confident that there is one in contract B ($85,000). Table IV-B shows the set of potential outcomes for the total revenue at risk across both contracts and their associated confidence. By using confidence values, we can draw a large number of outcome samples from a binomial distribution to create a probabilistic forecast. We can assume that when knowledge workers review a contract, the label’s confidence changes to 100%. More research needs to be conducted to investigate ways to capture realistic user confidence for more accurate projections. In figure 2, B) shows the distribution of possible total revenue at risk due to the presence of TFC clause in this set of contracts. As we can see, at this point in the reviewing process, the total revenue at risk is most likely around $1.6M. As users review more contracts, the range of possible values will get smaller and the confidence will increase. This approach allows for more detailed and transparent forecasting by communicating the range of possible values and uncertainty.

A) Select your reviewing parameters, get an overview of the set of contracts and track their reviewing progress B) Inspect the set of possible values of contracts with TFC clauses and their corresponding probability C) Review contracts by confirming or overriding the classifier recommendation. Every time a user reviews a contract, the confidence of the label identification is set to 1 and the projections in B) are updated.

We conducted a preliminary qualitative evaluation of our system with 4 knowledge workers recruited via an online testing platform. Our goal was to observe how knowledge workers use our system to reach a decision about revenue at risk. Knowledge workers were recruited if they read or reviewed contracts at least once a month, reviewed contracts pertaining to a relevant sector, were familiar with termination for convenience clauses, worked for a company in a relevant sector and in a relevant divisions

In our task, we asked users to predict the total revenue at risk due to the presence of Termination for Convenience (TFC) clauses across a set of 16 contracts identified by the hypothetical imperfect classifier described in section 3.1. Participants were shown a baseline interface that did not contain uncertainty information or outcome projections (see figure 3), and the DocSpect interface. Participants were given a definition of Termination for Conve- nience and shown examples of TFC clauses, followed by a short practice quiz that involved identifying TFC clauses. In the main task, participants were shown the baseline interface followed by the DocSpect interface preceded by an instruction video on how to use each interface. In both conditions, users were given a maximum of 3 minutes to report as accurately as possible the total revenue at risk due to the presence of TFC clauses across the contracts. After the time was up, the table of contracts disappeared but the rest of the information remained on the screen. The time limit of 3 minutes, determined through pilot studies, was chosen to replicate real world conditions where the set of contracts is too large for knowledge workers to review every single one. Users could end the task before the timer if they wished to do so. After each condition (baseline or DocSpect), users were asked to report their answer for the total revenue at risk due to TFC as well as their level of confidence. Then, they completed a task load comprising of three sub-scales of the NASA-TLX workload test, namely mental demand, performance and effort. Task load scores range between 5 (no effort at all) and 15 (maximum effort). They also completed a usability test.

When using both the baseline and the DocSpect interface, users reviewed the contracts in a sequential order from the table until the timer was over. When using the DocSpect interface, they did not use the reviewing parameters and did not adopt a particular reviewing strategy. This could be due to the time constraints imposed by the study design which caused the users to focus on reviewing the maximum number of contracts. One solution is to improve our system to have more explicit reviewing strategies that they can adjust, as well as an initial set of recommendations. Moreover, participants reported a high average total task load score of 14.25 when using DocSpect and 12.25 when using the baseline interface, and average usability scores were low for both interfaces. While they were reviewing contracts using DocSpect, users did not refer to the histogram, which shows the set of possible outcomes and their confidence. This could also be due to the additional time constraint of reading the graph. However, only one user used the histogram after the timer was up and still failed to report the value with the highest probability. This behavior could be due to poor understanding of uncertainty information, or poor uncertainty visualization literacy. Several studies have shown that it is difficult for people to understand uncertainty information [ 5], despite its value in facilitating evidence-based decision-making [7, 9]. In future system developments, we plan on revisiting ways to encourage users to consider the uncertainty information in their reviewing strategies and when reporting revenue. Moreover, the study design could be improved by allowing users to review only a portion of the set of contracts instead of imposing a time limit, which created time pressure.

While future work needs to be conducted to improve system fea- tures in DocSpect as well as the study design, our framework pro- vides a novel perspective, informed by knowledge workers work- flow, on ways to optimize contract reviewing strategies such that ensuing forecasting outcomes and business decisions are improved. We encourage researchers to consider the impact on decision- making when evaluating systems.